This article is part of the Library Series: Electronic History.

What you’ll learn:

- The history of VCRs.

- The technologies behind the creation of VCRs.

- The VCR’s eventual decline.

In today’s world, we rely primarily on streaming services to watch movies and TV shows at HD resolutions. Although a good portion of the population still takes advantage of Blu-ray players to watch media on giant-screen TVs, we’re no longer bound to watch entertainment at home. Mobile devices have allowed us to stream our favorite content on the go at resolutions that would be unheard of a few decades ago.

Technology has evolved at a rapid rate to get us to the point where we can access and stream or play media virtually almost anywhere. We needn’t be anchored in front of TVs. Technology evolved.

The digital media world, like most technologies, started life in the analog realm. Ask anyone over 35, and chances are they’ll reminisce about a time when giant plastic cassettes dominated living rooms and bedrooms. Where the familiar sound of rewinding and fast-forwarding, inserting and ejecting those tapes were the soundtrack to a seemingly bygone era.

Back in the 1970s, 80s, and much of the 90s, videocassette recorders (VCRs) were the pinnacle of home entertainment. Their popularity gave birth to giant rental chains, such as Blockbuster and Hollywood Video, where people waited in line to get the latest releases.

The VCR Has a National Day?

But would it surprise you to know that June 7 is National VCR Day? As strange as that may sound, it’s an unrecognized holiday, in much the same fashion as May the Fourth, but both are equally fun.

Before the celebration begins, let’s look back at the VCR’s humble beginnings and how it became the platform of choice spanning nearly three decades. For that, we have to travel all the way back to 1956, when Ampex introduced its VRX-1000, a $50,000 videotape recorder that was only accessible to television networks due to its insane price.

The machine was massive as well, using 2-inch reel-to-reel quadruplex videotape to store media, which was read by four magnetic record/play heads mounted on a headwheel spinning transversely (width-wise) across the tape at a rate of 14,386 rpm.

The Ampex recorder took advantage of the quadruplex format—it could produce extremely high-quality images with a horizontal resolution of around 400 lines per picture height. That’s noticeably lower when compared to PAL’s 625 lines, but it still produced high-quality images and remained the de facto industry standard for television broadcasting from 1956 to the mid-1980s.

In 1959, Toshiba unveiled a new method of recording known as helical scan, releasing the first commercial helical-scan video tape recorder that year. It was first used in reel-to-reel videotape recorders (VTRs) and later went with cassette tapes.

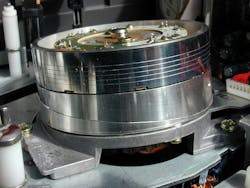

Helical-scan technology (Fig. 1) places the magnetic tape heads on a spinning drum that’s angled, allowing the head chips to read the tape diagonally faster than they would using flat reel-to-reel heads. These were eventually minimized with later technology and could be found in VCRs until their demise.

It wasn’t until 1963 that the first home video recorder was produced by UK-based Nottingham Electronic Valve Company, with the production of its Telcan (Television in a Can). The platform could be purchased as a unit or in kit form for around $1,700, or roughly $45,200 today, which meant it wasn’t found in most homes at the time.

Goodbye Reel-to-Reel, Hello Cassette

In 1969, Sony unveiled its videocassette prototype, and then put it on the backburner while the company went to make it an industry standard. By 1971, Sony introduced its U-matic system, the world’s first commercial videocassette format. The cartridges appear like larger versions of VHS tapes (Fig. 2), using 3/4-inch-wide tape (over the 2-inch reel-to-reel tape). Maximum playing time was 60 minutes, which was later extended to 80 minutes.

Shortly after the cartridge format breakthrough, videocassettes of movies were introduced on Cartrivision, a cassette format introduced by audio and video pioneer Frank Stanton of Cartridge Television Inc. His format wasn’t exactly practical, as Cartrivision came in the form of a TV set with a built-in recorder in order to play feature films. It was first introduced at CES 1970, sold through Sears, Macy’s, and Montgomery Ward in 1972, then faded away in 1973 due to poor sales.

Be that as it may, Cartrivision was a forgotten forerunner of the VCR. In 1971, Philips began developing a new format, which became available in the commercial market in 1972 under the name “video cassette recorder (VCR).” It was also referred to as N1500 after the model number of the first recorder machine.

It wasn’t until the mid-1970s that prices became affordable enough for home use. Several prominent tech companies flooded the market with superior platforms, and thus, the format war began between Sony’s Betamax and JVC’s VHS.

VHS vs. Betamax

History tells us what format emerged victorious, but for a while, both dominated the commercial market. Sony introduced the Betamax (Fig. 3) in 1975 in Japan before it was released in the U.S. later that year, where it became a hit with its sharper images and relatively compact design. JVC’s VHS, on the other hand, offered longer-playing cassettes at more affordable prices at the cost of reduced resolutions.

The science of that superiority can be broken down in terms of speed. The heads on the drum of a Betamax VCR move across the tape, producing a writing speed of 6.9 or 5.832 meters per second with the drum rotating at 1800 rpm (NTSC, 60 Hz) or 1500 rpm (PAL, 50 Hz). Theoretically, this gave Betamax a higher bandwidth of 3.2 MHz, thus providing better video quality than VHS.

We can also compare the two formats in terms of resolution. For example, initial Betamax tapes provided 250 lines (333×486p) of luminance resolution and 30 lines (40×486p) of chroma resolution, while VHS came in at 240 lines (320×486p) of luminance resolution and 30 lines (40×486) of chroma resolution.

Regardless of image quality, JVC employed a tactic that guaranteed them VHS victory: JVC opened the patent, enabling other companies to take advantage of its technology, leaving Sony in a proprietary freefall. Yes, Betamax lost the format wars, but Betamax didn’t become obsolete as recorders continued to be manufactured and sold until 2002, and Sony continued to manufacture Betamax tapes all the way through to 2016!

Enter the DVD

VCRs continued to dominate home media until the late 1990s and early 2000s, when DVDs became a successful medium that offered superior resolutions for pre-recorded videos. As DVDs came down in price, VCRs and VHS tapes became obsolete, and by June 2003, DVD rentals surpassed VHS.

By 2007, the FCC released a mandate declaring that all new TV tuners in the U.S. must include ATSC and QAM support, and it encouraged electronics manufacturers to end the production of standalone VCR units. To circumvent that encouragement, manufacturers began producing combo TVs with both VHS and DVD players, as consumers weren’t ready to sunset their collection of VHS tapes. The same practice was put into play for VCR/Blu-ray combo players as DVD players declined.

The very last hurrah for tape cassette home media was the D-VHS or Digital VHS. It held a digital video recording on the tape. The cassette tapes were capable of outputting 720p and 1080i resolutions. The tapes had a theoretical digital capacity of 50 GB! At regular 480p resolution, these tapes could hold up to 40 hours. It was quite a leap for the tech. However, little awareness, the proliferation of DVD, and the introduction of Blu-ray and HD-DVD stopped D-VHS in its tracks. Only 91 movie titles came out for D-VHS. For comparison, Laser Disc had over 8000 titles.

A Nostalgic Future for VCRs?

So, where does that leave VCRs in the new millennium, and are they set for a comeback? It’s unlikely they’ll reach the resurgence of LP players and vinyl records, which upper-echelon audiophiles have made popular again. It’s also not profitable for manufacturers to produce VHS tapes while in the throes of the digital revolution, but all hope isn’t lost.

There are still those who prefer the nostalgia of watching movies in analog form and reminiscing over family videos. The fact that you can still buy VHS movies on eBay, at yard sales, and in pawnshops provides proof to that testament.

Do you all still have a VCR and tapes? Sound off in the comments below.

Read more articles in the Library Series: Electronic History.